By Alyssa Nickerson

You may have noticed from the title that I am attempting something highly questionable. Controversial. Not the sort of thing, for instance, to bring up at a Savannah socialite’s dinner party, at least not until after far too many mint juleps.

Then again, Lucky Savannah doesn’t cater to the average tourist. In our minds, the visitor is unique, complex, intriguing — the same qualities you can find in our rental properties. So here’s the scoop — and let’s keep this quiet, y’all — there is a literary history to Savannah that stretches beyond The Book. (And no, I do not mean the Bible; in Savannah, that moniker refers to John Berendt’s classic: Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil.)

Ready to turn the page?

Flannery O’Connor’s Childhood Home

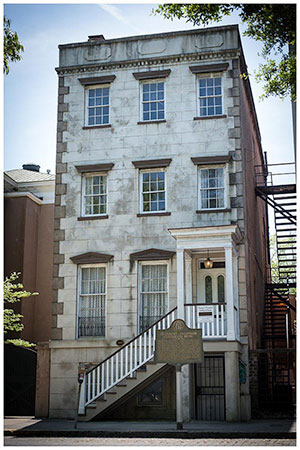

Nestled on a quiet boulevard overlooking Lafayette Square is a grand stone townhouse. The narrow home is unadorned but for a whitewashed flight of stairs, four rectangular reliefs that crest the monolithic bricks one of the ubiquitous green-and-bronze plaques that mark Savannah’s historical treasures.

Behind the curtained French windows, slightly warped from the wear of time, one of America’s greatest authors held court over her cherished “chicken yard” in her youth.

Most famously, the young Mary Flannery taught one of these beloved fowls to walk backwards; as a result, she and the chicken were pictured in the local paper. In an oft-quoted bit of wit, she claims everything in her life after her that moment was an anticlimax: her three O’Henry Awards did not hold any of the same charm for the witty Southern wordsmith.

The essence of the home has been restored to the Depression era; the general ambiance, as well as a bit of Flannery O’Connor’s unassuming grace, is beautifully captured in a poem by Diane Scholl.

I had the time and luck to speak with a touring artist, Tim Youd, who in the pursuit of his 100 Novels Project recently traveled to Savannah. The typing of two of O’Connor’s most famous works — The Violent Bear It Away and Wise Blood — brought him to both nearby Andalusia, her ancestral and adult home, and to the Childhood Home. Upon his first night in the house on Charlton Ave., he enthused, “I may never leave!”

In 2010, the recently deceased Pat Conroy also lauded that the house should be known as “one of the temples of world literature” while announcing finalists for the National Book Awards.

With those reviews, how can you help but drop in for a spell?

Conrad Aiken

The next chapter in our saga involves an eloquent and amusing modernist American poet.

Conrad Aiken attended T.S. Eliot’s cohort at Harvard and mixed with the same literary circles, but faded out whereas Eliot became a legend. (This is not due, however, to skill: Aiken’s poems are sometimes surreal, often haunting, funny, and deeply moving.)

Before this, however, he was born and partially raised in this city — until tragedy struck the prominent Aiken family. His father, a respected surgeon, suddenly fell prey to fits of mood when Conrad was only eleven years old. One morning, the young poet woke to yelling from his parents’ bedroom; the clamor ended in gunshots. He walked to their room and discovered the bodies; he never escaped this sight. Their house on Oglethorpe Lane, across from Colonial Cemetery, still bears a placard out front.

Throughout his life, Aiken would often worry that he would wind up in the clutches of a similar madness. Instead, he became a renowned American writer; his oeuvre contains poetry, short stories, novels, a play, and an autobiography.

He also received a wealth of awards during his lifetime, among them the 1930 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry, the Bollingen Prize, a Guggenheim Fellowship, the 1954 National Book Award for Poetry. Aiken also served as Poet Laureate in 1950.

He eventually returned to Savannah and is buried in Bonaventure Cemetery, beside his parents. His gravestone is one of Savannah’s most unique attractions: shaped as a marble bench, it sports two engraved phrases: on the left, “Cosmos Mariner: Destination Unknown,” and on the right, “Give my love to the world.”

A beautiful view of the river and lush azaleas completes the calm scene. Feel free to bring a book!

Okay, so maybe a little Berendt…

While at Bonaventure, it couldn’t hurt to check out the famous statue of the Bird Girl — after all, the cemetery did inspire the poetic, macabre title of Berendt’s bestseller.